One of the most significant challenges in the management of sepsis is diagnosing it accurately and early when appropriate interventions can have the greatest impact. Clinicians, especially those working in emergency departments where most sepsis cases enter the healthcare system, are continually being challenged to identify septic patients sooner while distinguishing them from patients with more benign infections and other conditions that can mimic sepsis.

Unlike other dangerous conditions where blood tests can quickly and precisely identify the problem, for example, troponin in myocardial infarction, sepsis does not have an exact test. To make the diagnosis, clinicians have traditionally relied on many factors such as clinical symptoms, vital signs (eg, temperature, heart and respiratory rate), infection indicators (chest x-rays, urinalysis, cultures), and non-specific laboratory tests like CBCs, arterial blood gas, metabolic panels, coagulation studies and organ function panels (eg, renal, hepatic).

Given the great need for a more precise sepsis test, various molecules and other parameters have been studied for their potential to serve as sepsis biomarkers. These include metabolic indicators like lactate, acute phase reactants (eg, C-reactive protein [CRP], procalcitonin [PCT], ESR), immune modulators like interleukins (eg, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10), growth factors like angiopoietin, immune mediating soluble receptor molecules (eg, suPAR, sTREM-1, sCD-14/presepsin) and novel hematologic parameters that measure subtle changes in leukocyte morphology (eg, MNV, MDW). Among these, lactate, CRP and PCT have gained the widest acceptance in the clinical setting, while many of the others remain experimental or are only now reaching clinical use.

To explore the current state of sepsis biomarkers in the clinical setting, ESCAVO surveyed our Sepsis Clinical Guide app users with a few questions about which biomarkers they use, and why and how they use them. This article discusses the findings of this survey.

Sepsis Biomarker Survey Results

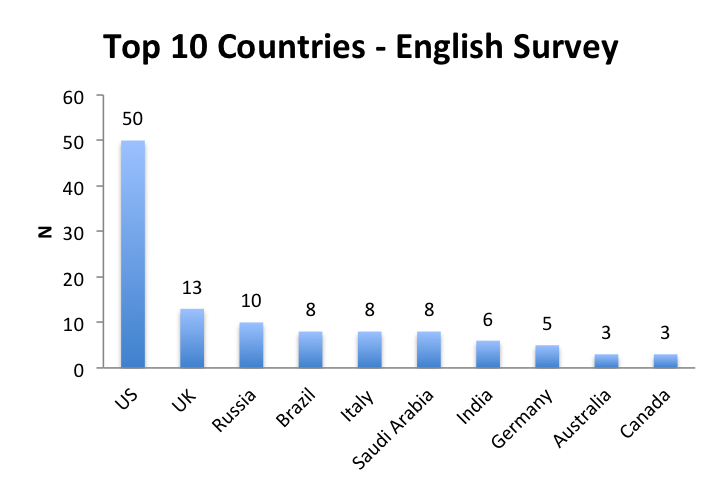

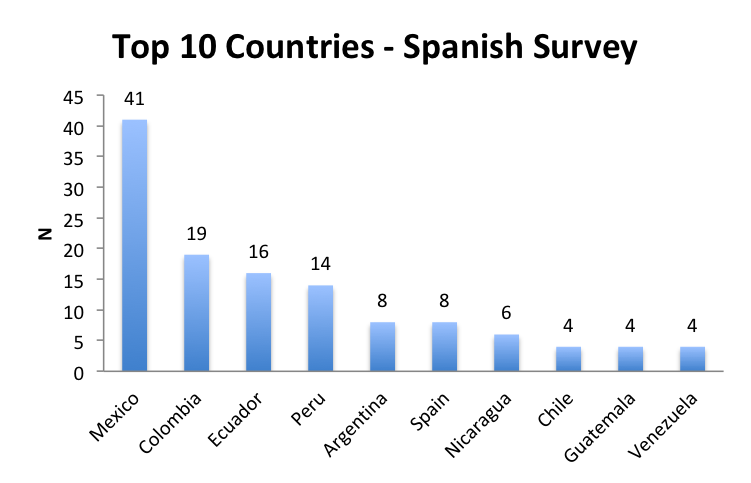

We conducted our survey between January 27th and February 20th, 2019 in the English and Spanish versions of our app, and received a total of 295 responses, 159 in the English language survey and 136 in the Spanish language survey. Forty-one widely distributed countries were represented in the English survey, with the US, UK, Russia and European countries having the most responders. In the Spanish survey, 17 countries were represented primarily in Central and South America, with Mexico, Columbia and Ecuador having the most responders. This section presents the results of our survey. To underscore some interesting geographic differences, we will show the overall responses as well as the individual English and Spanish survey responses.

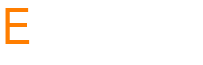

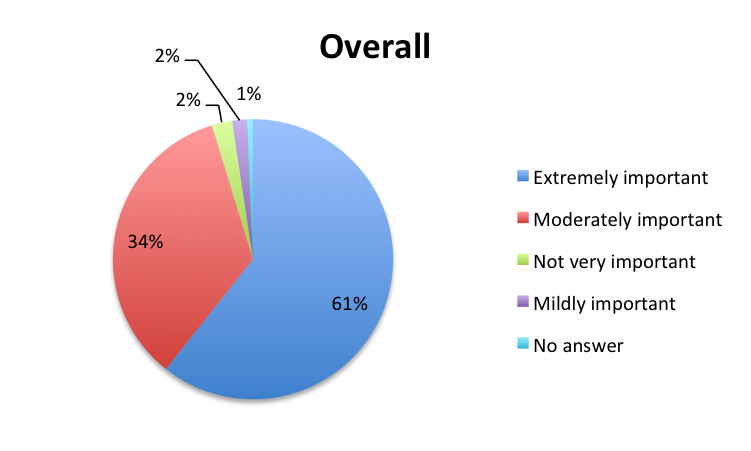

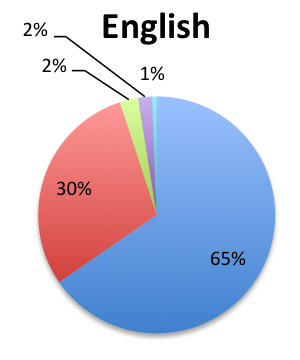

Question 1. In your clinical experience, how important are sepsis biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of sepsis?

A. Extremely important

B. Moderately important

C. Mildly important

D. Not very important

|

|

|

|

Question 2.What is the primary role of biomarkers in your management of sepsis?

A. They help me diagnose sepsis earlier

B. They help me assess sepsis severity and prognosis

C. They help me assess therapy response and guide treatment changes

D. All of the above

|

|

|

|

Question 3. Which biomarkers do you routinely use in your management of septic patients? (check all that apply)

A. Lactate

B. Procalcitonin

C. CRP

D. None

E. Other: Please specify

|

|

|

|

|

|

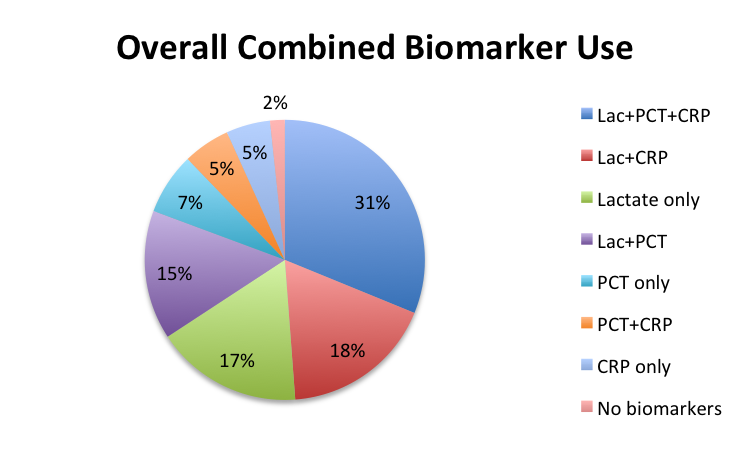

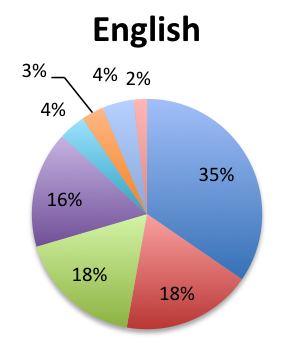

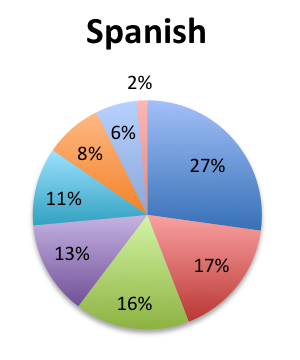

| Note: Although not shown in these charts, 6 responders overall (2%) also indicated using presepsin, in 5 cases in combination with lactate, PCT and CRP; and in 1 case only in combination with procalcitonin. In addition, 1 responder indicated using IL-6 in combination with the other 3 major biomarkers. | |

Question 4. Select the option that best describes how you use lactate in managing sepsis:

A. Support the initial diagnosis of sepsis and assess severity

B. Check tissue perfusion status and risk of organ dysfunction

C. Guide fluid resuscitation and assess treatment response

D. All of the above

E. I do not test for lactate/test not available in my practice

|

|

|

|

Question 5. Select the option that best describes how you use procalcitonin in managing sepsis:

A. Support the initial diagnosis of sepsis and assess severity

B. Differentiate bacterial sepsis from other types of sepsis or inflammatory states

C. Guide antibiotic therapy and assess treatment response

D. All of the above

E. I do not test for procalcitonin/test not available in my practice

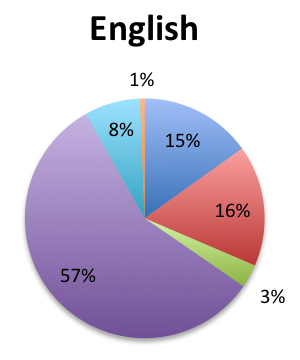

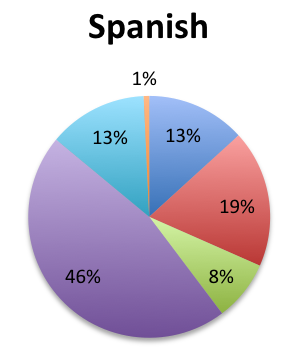

|

|

|

|

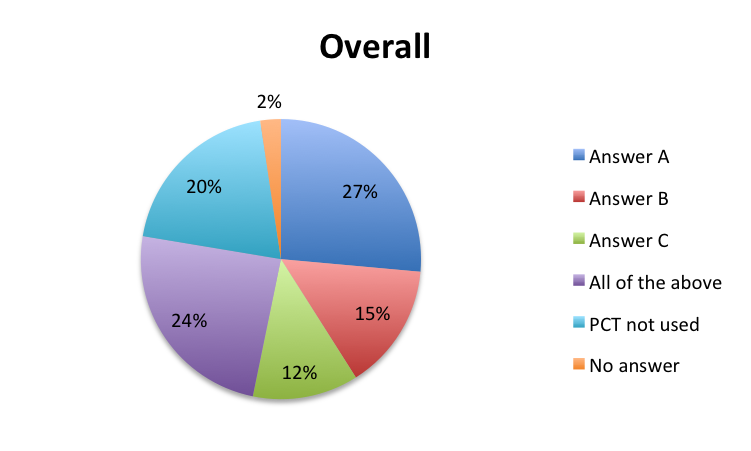

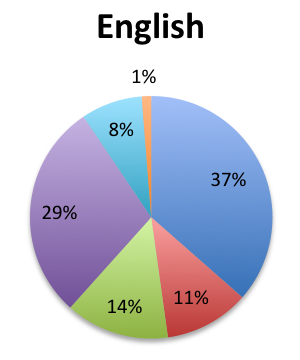

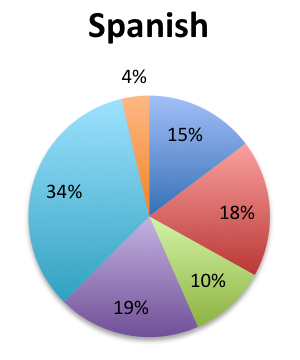

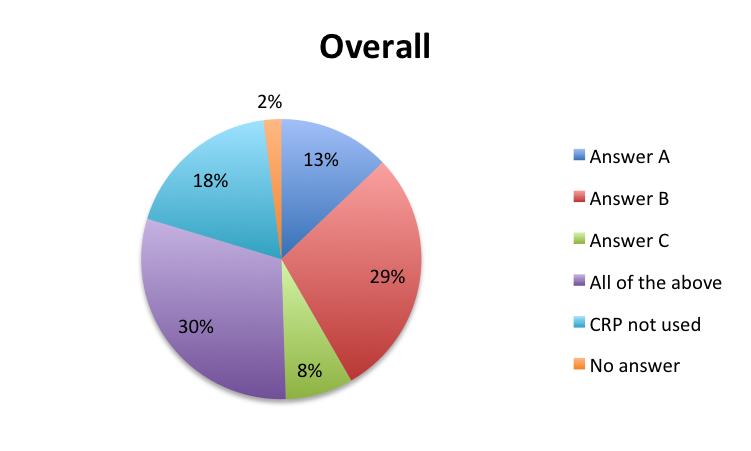

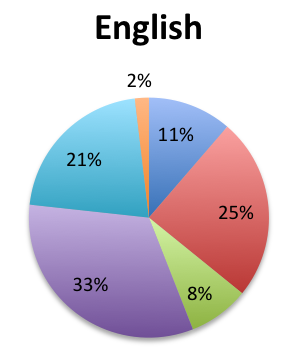

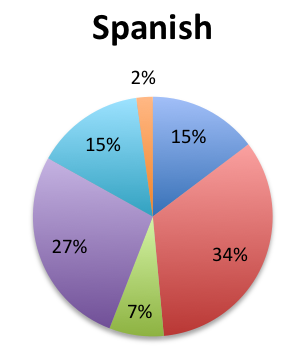

Question 6. Select the option that best describes how you use CRP in managing sepsis:

A. Support the initial diagnosis of sepsis and assess its severity

B. Assess the patient’s inflammatory state and prognosis

C. Guide antibiotic therapy and assess treatment response

D. All of the above

E. I do not test for CRP/test not available in my practice

|

|

|

|

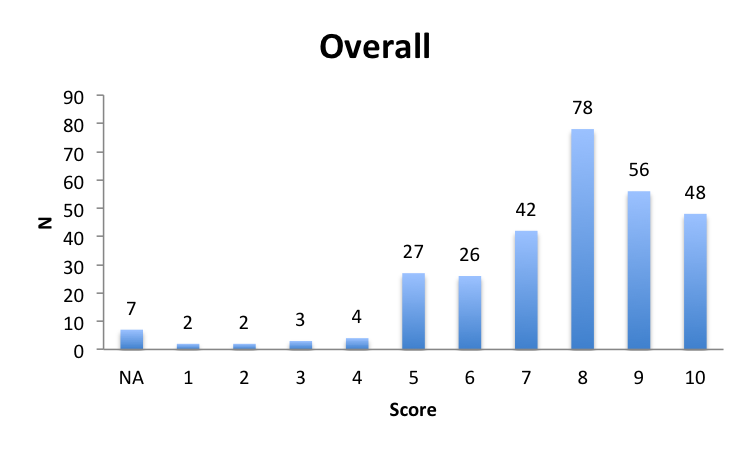

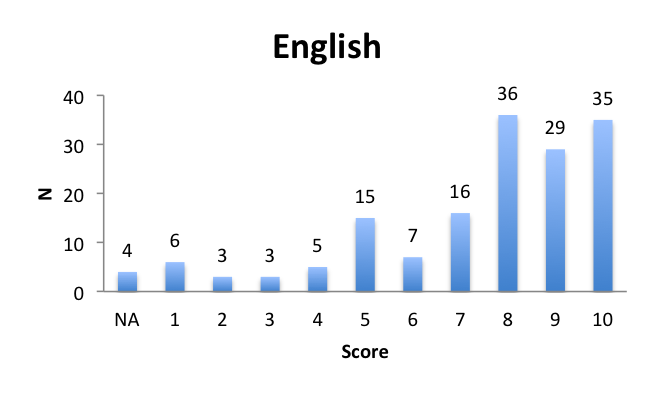

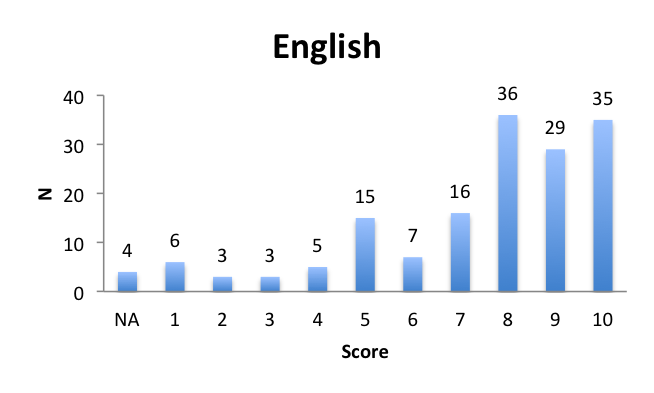

Question 7. On a scale from 1 to 10, how effective do you believe current sepsis biomarkers are in facilitating the early diagnosis of sepsis? (1=worst, 10=best)

|

|

|

|

| Average score: 7.4 | Average score: 8.2 |

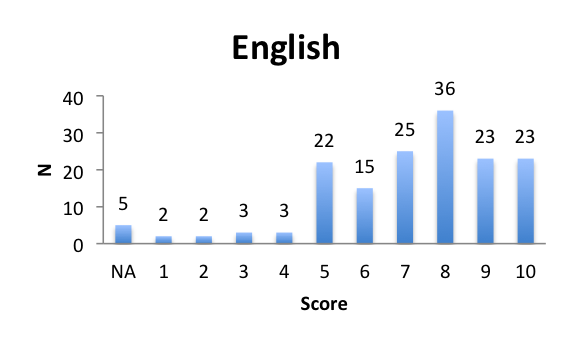

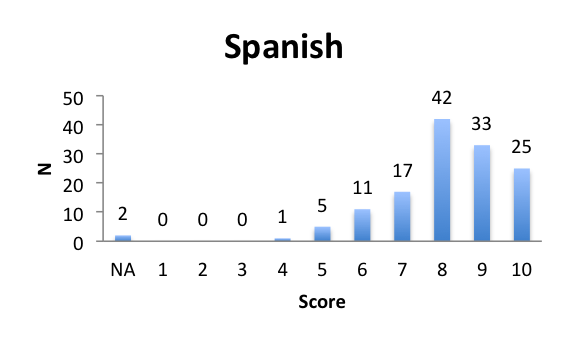

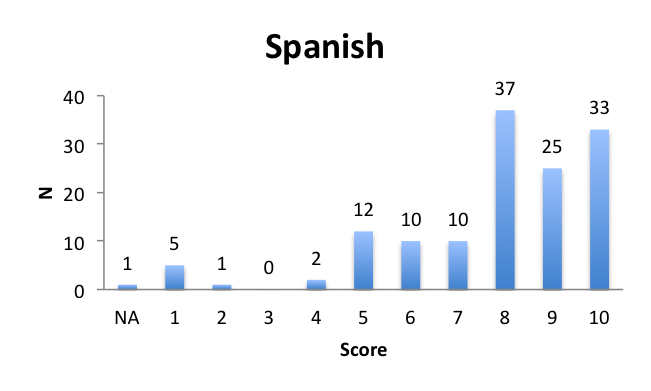

Question 8. On a scale from 1 to 10, how effective do you believe current sepsis biomarkers are in the assessment of sepsis severity and prognosis? (1=worst, 10=best)

|

|

|

|

| Average score: 7.3 | Average score: 8.3 |

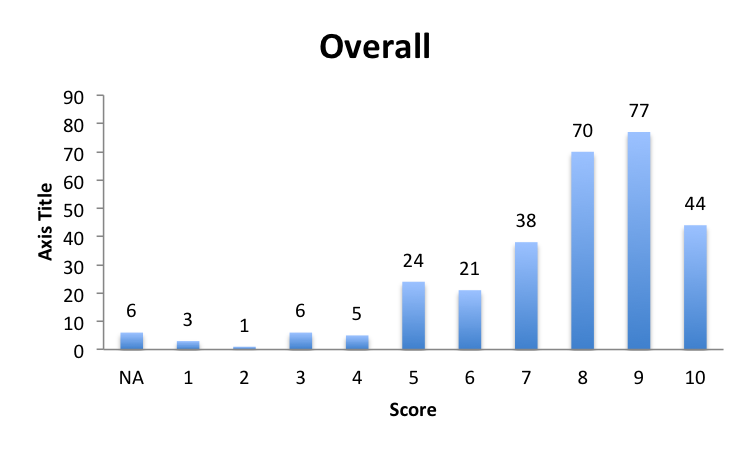

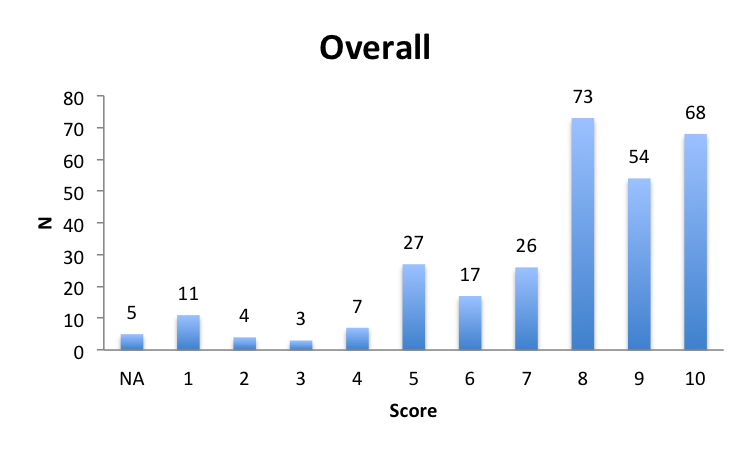

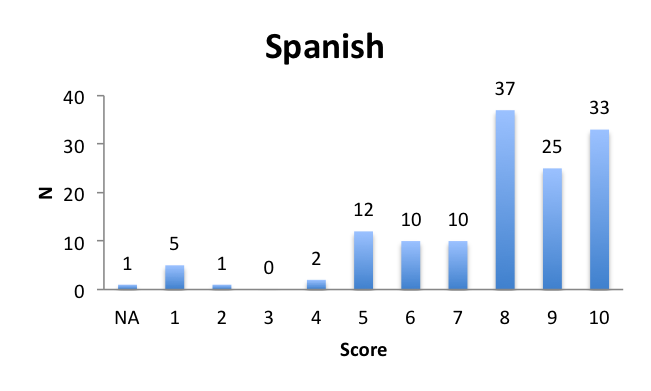

Question 9. On a scale from 1 to 10, how often do you use serial biomarker testing to guide/adjust your management of septic patients? (1=never, 10=very often)

|

|

|

|

| Average score: 7.5 | Average score: 7.8 |

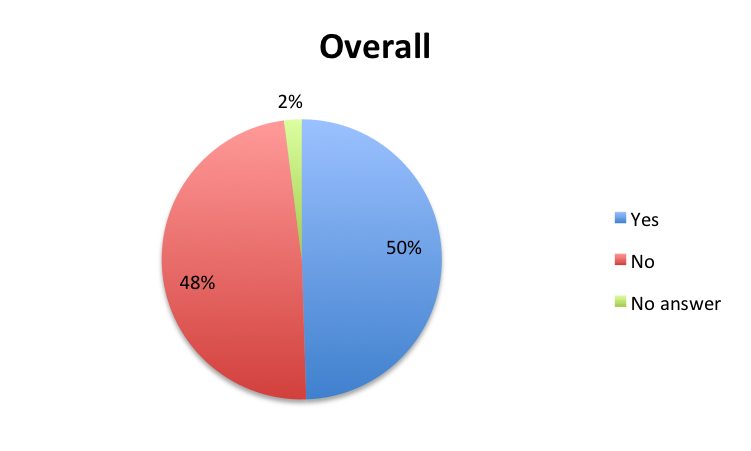

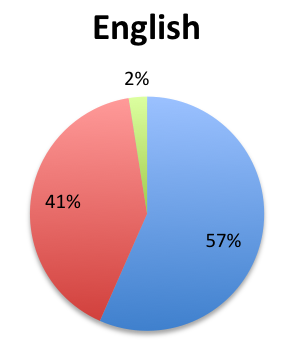

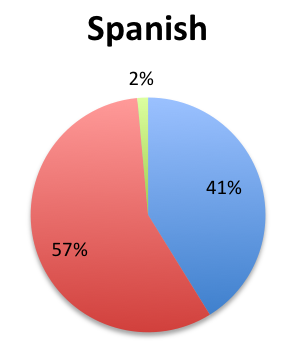

Question 10. Aside from “band cells”, does your diagnosis of sepsis use other leukocyte parameters like the immature granulocyte (IG) count or morphometric parameters such as neutrophil or monocyte mean volume or distribution widths?

A. Yes

B. No

|

|

|

|

Question 11. Please enter any additional comments you may have about sepsis biomarker tests (eg, comments on your use of biomarkers, thoughts on existing or novel biomarkers, future directions in this area, etc.):

| English Survey Comments* |

|

| Spanish Survey Comments* |

|

| *Comments have been revised for clarity and translated where needed. |

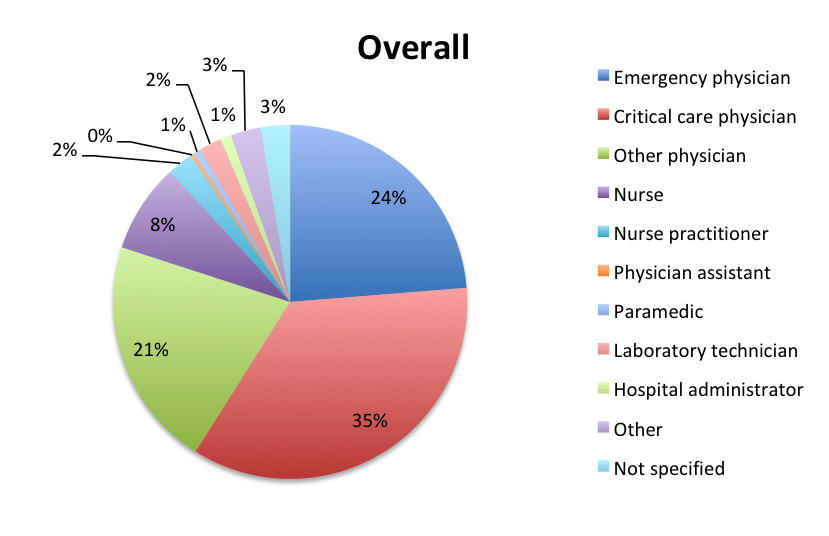

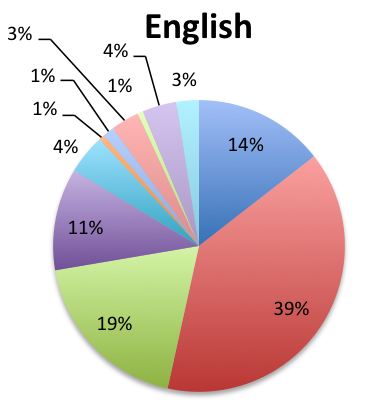

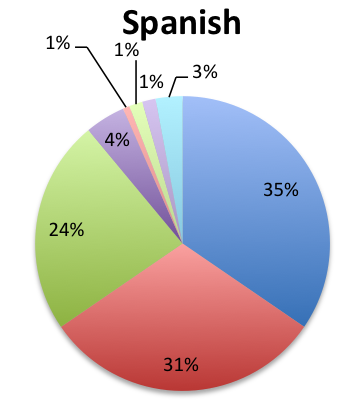

Question 12. Please select the choice that best describes your role:

A. Emergency medicine physician

B. Critical care physician

C. Other physician

D. Nurse

E. Laboratory technician

F. Hospital administrator

G. Other: Please specify

|

|

|

|

Participating countries

|

|

Results Analysis

The vast majority of survey responders, comprised of mainly physicians and nurses (88%), indicated that biomarkers are an essential part of sepsis management, with 95% of the 295 responders reporting that biomarkers are “extremely important” or “moderately important.” Somewhat fewer responders in the Spanish survey, which represented primarily Latin America, thought that sepsis biomarkers were “extremely important” (55% vs. 65% in the English survey), but the overall sentiment was nonetheless very positive.

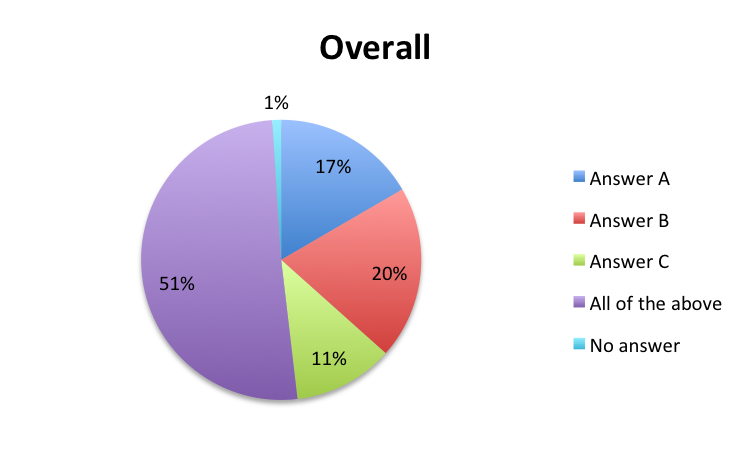

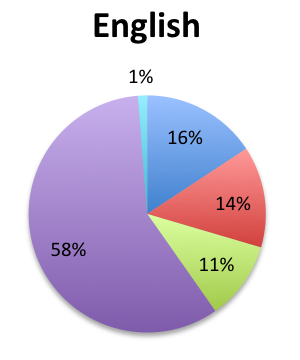

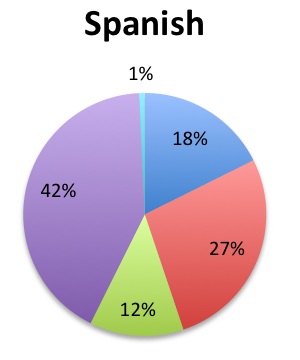

A majority of responders (51%) indicated using sepsis biomarkers for a variety of reasons including to facilitate early diagnosis, assess sepsis severity and prognosis, and gauge the response to therapy and guide treatment changes. Similar proportions of responders answered that they use biomarkers only to facilitate earlier diagnosis or to assess sepsis severity and prognosis (17% and 20%, respectively), and only 11% of responders answered that they use biomarkers primarily to gauge treatment response and guide treatment changes. A markedly higher percentage of responders responded that they use biomarkers primarily to assess sepsis severity and prognosis in the Spanish survey than the English survey (27% vs. 14%). These responses suggest that although clinicians use biomarkers for a variety of reasons, these tend to be primarily used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes rather than to guide treatment.

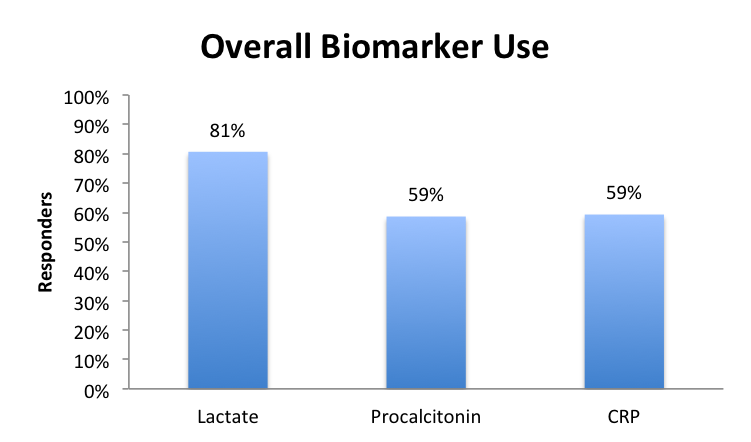

Lactate was the most commonly used biomarker with 81% of all responders reporting using it, followed by PCT and CRP each used equally by 59% of all responders. In terms of biomarker combinations, the largest segment of responders (31%) indicated using all three major biomarkers – lactate, PCT, and CRP – while considerably fewer responders reported using only lactate+CRP (18%) or lactate+PCT (15%). About 17% of all responders answered that they only use lactate. Somewhat fewer responders reported using all three biomarkers in the Spanish survey than in the English survey (27% vs. 35%), suggesting lower biomarker penetration in Latin America. Interestingly, a significantly higher percentage of responders in the Spanish survey noted using PCT alone (11% vs. 4%). Six responders (2%) also indicated using presepsin, while one responder indicated using IL-6, most often in combination with the three major biomarkers.

Although the sample was too small to provide meaningful granularity on biomarker use at the country level, a few interesting trends emerged. In general, responders in most countries used lactate and had a balanced preference for PCT and CRP. However, the UK and Peru tended to favor CRP over PCT, whereas the US tended to favor PCT. Interestingly, the majority of presepsin users were found in Eastern European countries including Serbia and the Czech Republic.

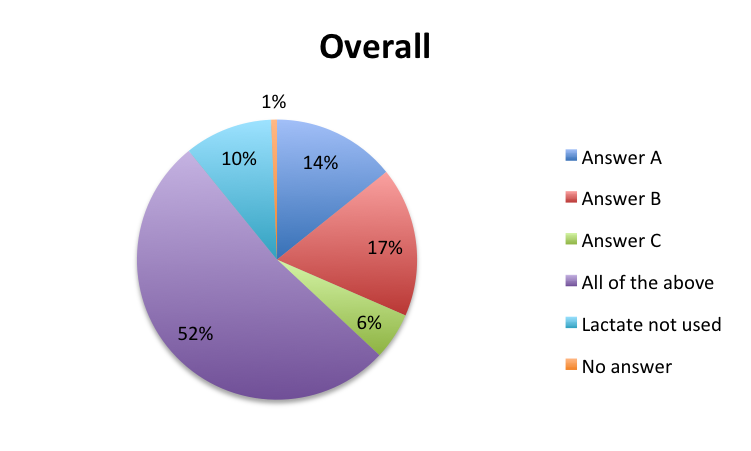

With regards to lactate, the majority of responders (52%) indicated using lactate for diverse reasons including to support the diagnosis of sepsis and assess its severity, assess perfusion status and risk of organ dysfunction, and guide fluid resuscitation and assess treatment response. Few responders indicated using lactate solely to guide fluid resuscitation (6%), with considerably fewer in the English survey (3%) than the Spanish survey (8%).

The reasons given for using PCT were somewhat more nuanced than for lactate. Only 24% of responders reported using PCT for all three reasons given, whereas 27% reported using it only to support making an initial diagnosis and assessing sepsis severity. Notably, there was a marked difference between English and Spanish responders concerning the use of PCT for initial sepsis diagnosis and severity assessment, with 37% of English responders indicating using PCT for this reason vs. only 15% of Spanish responders. On the other hand, Spanish responders reported higher use of PCT for differentiation between bacterial and other types of sepsis and inflammation (18% vs. 8%), and lower use of PCT for all given reasons (19% vs. 29%). Overall, 12% of responders reported using PCT solely to guide antibiotic therapy and assess response, with this group being somewhat similarly sized in the English and Spanish surveys, 14% and 10%, respectively. Of note, a far higher percentage of Spanish responders (34%) indicated not using PCT at all vs only a small percentage (8%) of English responders, perhaps suggesting lower availability of this biomarker in Latin America.

Similar to PCT, responders tended to report using CRP for specific reasons, in this case, primarily to assess the patient’s inflammatory state and prognosis (29%). Only 13% indicated using CRP for initial diagnosis, 8% to guide antibiotic therapy, and 30% for all three reasons. Spanish responders reported higher use of CRP to assess inflammation than English responders (34% vs 25%), and fewer of them indicated not using CRP at all (15% vs 21%). These findings suggest a preference for, or a higher availability of, CRP in Latin American countries vs other parts of the world, except for the UK, where CRP was also heavily favored.

Responders had a favorable view of sepsis biomarkers’ ability to facilitate the early diagnosis of sepsis, with English survey responders giving biomarkers an average score of 7.4 out of 10 in this regard, and Spanish survey responders giving a score of 8.2. For the quality of being able to asses sepsis severity and prognosis, biomarkers scored 7.3 in the English survey and 8.3 in the Spanish survey. Responders also indicated using serial biomarkers to guide and adjust the management of septic patients, with use scores being 7.5 in the English survey and 7.8 in the Spanish survey.

Finally, we examined clinical experience with new hematologic biomarkers, such as immature granulocyte count and leukocyte morphometric parameters, which are increasingly being used in sepsis management. Overall, only about half of responders reported using such biomarkers in sepsis, with the percentage of users being somewhat higher in the English survey vs. the Spanish survey (57% vs. 41%).

Discussion

The results of our survey confirmed that most clinicians view sepsis biomarkers favorably and use them extensively in their management of sepsis. Responders gave biomarkers moderate-to-high grades for their ability to help diagnose sepsis earlier, assess its severity and prognosis, and help guide its treatment. In general, survey responders reported using biomarkers for a variety of diagnostic, prognostic and treatment purposes, while appearing to prefer specific biomarkers over others in some cases.

Lactate was the most widely used biomarker, not surprising given its place in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) 1-hour sepsis bundle, and SSC recommendations for using it to guide initial resuscitation. (1, 2) Many responders reported using lactate in all areas of sepsis management including diagnosis, prognosis and treatment, but primarily to support the initial diagnosis and assess the patient’s perfusion status. Although the mechanisms that cause a rise in lactate in sepsis are complex and not completely understood, including not only tissue hypoperfusion, but also decreased liver clearance, and endogenous and exogenous catecholamines (3, 4), what is certain is that persistently high lactate is associated with poorer outcomes and increased mortality. (5)

PCT and CRP were used by fewer, but still over half of the responders and in equal proportions. Most responders reported using all three biomarkers, while fewer responders used lactate plus PCT or CRP, and fewer still only one biomarker, typically lactate. PCT appeared to be favored for early diagnosis, while CRP as a general marker of inflammation, although responders also reported using these biomarkers to support the initial diagnosis and to guide treatment. We should note that PCT is highly recommended for monitoring antibiotic effectiveness and supporting antibiotic de-escalation and stewardship (6), which was also a reported use, but not necessarily the main reason for use. Overall, the reasons given for using these sepsis biomarkers were mostly consistent with current guidelines and recommendations.

In general, most countries tended to widely use lactate and be reasonably well balanced in their use of PCT and CRP. However, interestingly, some countries appeared to have a preference for certain biomarkers, notably the UK and Peru for CRP over PCT. In the case of the UK, this is likely caused by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendation for CRP as a sepsis biomarker over PCT in its sepsis guideline. (7) The cause for a strong preference for CRP in Peru is uncertain, it may be due to specific local reasons, an orientation towards UK guidelines, lack of PCT availability, or a sampling anomaly caused by the small sample size.

About four times as many responders in the Spanish survey reported not using PCT, indicating that PCT is far less used in Latin America, the principal region covered by the Spanish survey, than in other parts of the world. We should note that this also applied to Brazil, a country that was primarily sampled in the English survey. Spain, the only non-Latin American country in the Spanish survey, however, appeared to show a slight preference for PCT, although the sample size was very small. Given that it is unlikely clinician preferences alone could account for such a discrepancy, a plausible explanation for this finding is the lack of PCT availability in Latin America, perhaps due to resource limitations. On the other hand, the rest of the world, and especially the US, showed a preference for PCT, with about 30% more responders indicating not using CRP in the English survey.

One of the survey’s more interesting findings was the use of new emerging sepsis biomarkers like presepsin, with several responders indicating using this new biomarker, most commonly in addition to the other three biomarkers. Presepsin, otherwise known as sCD-14, is a soluble receptor for lipopolysaccharides (LPS), the endotoxins released by Gram-negative bacteria, and also for Gram-positive cell wall components LAM and HSP-60. This soluble receptor is released by activated monocytes, the immune system’s sentinel cells. (8) Studies have found presepsin to be a promising sepsis biomarker, and assays are now becoming available for clinical use in some parts of the world. (9) One responder also reported using IL-6, a pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine released by activated monocytes and macrophages (and other cells) that has shown promising results as a sepsis biomarker. (10) One meta-analysis of IL-6 found it to be a highly accurate diagnostic modality for sepsis identification with a sensitivity of 80%, a specificity of 85% and an AUC of 0.868. (11)

We also surveyed responders on their use of hematologic parameters such as the immature granulocyte (IG) count and novel leukocyte morphometric parameters such as neutrophil and monocyte mean volumes and distribution widths. Much like the “band cell” count, which is a part of the SIRS criteria, the idea behind the IG count is to detect immature neutrophils whose presence in the blood may indicate a bacterial infection. The leukocytes counted in the IG count, however, are earlier precursors to band cells that include promyelocytes, myelocytes and metamyelocytes. Automated IG counts are now available in modern hematology analyzers, but IG count values above a certain user-defined percent threshold still typically trigger a manual blood smear review that may prompt a manual differential. (12, 13)

Leukocyte morphometric parameters more precisely measure deviations in the size and size distribution of specific WBCs like neutrophils and monocytes which are seen in infections. A number of studies have identified increased mean neutrophil and monocyte volumes and distribution widths as potential indicators of sepsis. (14, 15) The monocyte distribution width (MDW), in particular, has been found to be a promising sepsis biomarker. (16) It is likely that the same monocyte activation mechanisms that cause a release of sCD-14 (presepsin) during sepsis are also responsible for the increase in monocyte size that is detected by this morphometric test.

In our survey, only about 50% of responders indicated using these novel hematologic parameters in their management of sepsis, but we did not probe which specific parameters were used. In a future survey, we may further investigate these new promising hematological sepsis biomarkers.

Conclusion

Our survey of 295 healthcare professionals from 59 countries, primarily emergency medicine, critical care and other physicians, indicated that sepsis biomarkers are an important component of clinicians’ armamentarium in modern sepsis care. Responders scored sepsis biomarkers moderate-to-high in their ability to facilitate early diagnosis, assess severity and prognosis, and guide therapy, and reported diverse use in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of sepsis. Lactate was used most frequently and for a broad range of diagnostic, prognostic and treatment reasons, whereas PCT and CRP tended to be used less frequently and for more specific reasons. PCT tended to be used as an early diagnostic test, and CRP as a marker of inflammation. Most clinicians used all three major biomarkers, with fewer using only two, lactate plus PCT or CRP, or lactate alone. Geographic disparities were noted in biomarker use, specifically, less use of PCT in Latin America likely due to lack of availability. Although the sample size was small, some biomarker trends were noted at the country level, specifically, higher use of CRP over PCT in the UK and Peru, and higher use of PCT over CRP in the US. Emerging biomarkers like presepsin were also reported by some responders, and about half of responders reported using hematologic parameters like the IG count and leukocyte morphometric parameters, although the exact parameters used were not surveyed.

Daniel Nichita, MD

References:

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign 1-Hour bundle (Article)

- Rhodes A, Evans L, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2016. Crit Care Med 2017;45(3):486-552. (Article)

- Hernandez G, Bellomo R, Bakker J. The ten pitfalls of lactate clearance in sepsis. Int Care Med. 2019:45(1):82-85. (Article)

- Omar S, Burchard AT, Lundgren AC, et al. The relationship between blood lactate and survival following the use of adrenaline in the treatment of septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011 May;39(3):449-55. (Article)

- Bakker J. Lactate is THE target for early resuscitation in sepsis. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2017 Apr-Jun;29(2):124-127. (Article)

- Chanu Rhee. Using Procalcitonin to Guide Antibiotic Therapy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017 Winter; 4(1): ofw249. (Article)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sepsis: Recognition, assessment and early management. NICE Guideline 51. July 2016. (Article)

- Shive CL, Jiang W, Anthony DD, Lederman MM. Soluble CD14 is a nonspecific marker of monocyte activation. AIDS. 2015 Jun 19; 29(10): 1263–1265. (Article)

- Jing Zhang, Zhi-De Hu, Jia Song, Jiang Shao. Diagnostic Value of Presepsin for Sepsis. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Nov; 94(47): e2158. (Article)

- Molano Franco D, Arevalo‐Rodriguez I, Roqué i Figuls M, Zamora J. Interleukin‐6 for diagnosis of sepsis in critically ill adult patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 7. (Article)

- Hou T, Huang D, Zeng R, et al. Accuracy of serum interleukin (IL)-6 in sepsis diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(9):15238 – 15245. (Article)

- Senthilnayagam B, Kumar T, Sukumaran J, et al. Automated Measurement of Immature Granulocytes: Performance Characteristics and Utility in Routine Clinical Practice. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:483670. (Article)

- Loafman Mary Anne. Advanced clinical parameters: achieving efficiency with automated immature granulocyte count. Medical Laboratory Observer. Feb. 29, 2019. (Article)

- Park DH, Park K, Park J, et al. Screening of sepsis using leukocyte cell population data from the Coulter automatic blood cell analyzer DxH800. Int J Lab Hematol. 2011 Aug;33(4):391-9. (Article)

- Lee SF, Kim SG. Mean cell volumes of neutrophils and monocytes are promising markers of sepsis in elderly patients. Blood Res. 2013 Sep;48(3):193-7. (Article)

- Crouser ED, Parrillo JE, Seymour C, et al. Improved Early Detection of Sepsis in the ED With a Novel Monocyte Distribution Width Biomarker. CHEST. 2017 Sep;152(3):518–526. (Article)